Auld lang syne*

And welcome to this newsletter.

It's where I (John Surico) talk each month about cities & their discontents: streets, climate, cultures, people, food, form, etc. This month, we cover:

- Semester-end climate reporting;

- Leveling up public works;

- An ode to the alt-weekly;

& much, much more.

Programming note: I’ve been having a debate lately with friends: when was the last year that felt normal? Normal is relative, of course, but here, it means a year where our shared reality didn’t feel so dissimilar; where it didn’t feel like things were just ever so slightly off — in our politics, in our world, in our facts, in our fictions. Normal, in a sense, is the Nineties; this decade of what most would consider a steady culture. (Think of how most movies from this time even look alike.) We wax nostalgia for that time, if only for how low the stakes all seemed.

In terms of normal, I peg its departure somewhere around 2014. Much like how 9/11 was the brutal start of modernity, the mid-2010s felt like the start of something… else. A ‘new normal,’ to recycle the pandemic-era phrase, when the Internet finally broke our brains, nationalism finally broke our postwar liberal order, and the climate finally broke our bravado of living on this planet without material consequence. That’s when things got weird.

By that measure, 2024 is ten years into the upside-down. And it felt like it — this permanent pendulum swing of upheaval, confusion, and strife. John Lennon’s “Happy Xmas (War is Over)” is typically so profound around the holidays with its pleas for peace, but this year, a blank stare felt more appropriate. Because that “new normal” now feels normal. Locally, I see it in how we talk about everything from election results and enveloping global conflict, to the fatal shooting of a major healthcare company CEO and an unhoused woman being lit on fire while asleep on the subway — headlines met with shrugs, if not murmurs that nothing, really, surprises us anymore, or so we reassure ourselves.

We’re living in a time when so much is changing, so much is uncertain, and so much can happen. (Exhibit F: March 2020.) This newsletter, of course, looks at that last bit with a glass-half-full approach, even if it can appear so empty. It’s an attempt, maybe for my own sake, to talk through what we’re collectively experiencing, and what it means for the places we live in. Because while these may be strange days, the capacity to be and remain inspired is as important as ever. It unsticks us from that paralysis, spurring us to care, to act, and to leave behind a better world than the one we found.

Alongside my loved ones, that’s where I’m finding joy this holiday season — and I hope you can, too, reader. Cheers to 2025.

Climate generation

Practically every news outlet now has some version of a ‘climate reporter.’ Although in 2024, I’d argue that most reporters are, in some sense, on the climate beat. Because its changes — and what we must do to adapt to and mitigate them — infest everything we know: housing, transit, politics, breaking news, etc. Thus, journalism school should prepare accordingly.

For undergrads at NYU Journalism, we didn’t have anything specifically dedicated to what, I think, is the biggest challenge facing us today. That seemed bizarre to me. So, for some time now, I’ve been trying to get a reporting class going that was wholly focused on the climate crisis and New York City to fill that gap. Thankfully, the department agreed, and I finally got the opportunity this semester, with a new course we called “The Beat: Climate City.”

The backdrop (unfortunately) did not disappoint. You had storms that ripped through the South, destroying many of the regions the students hailed from. You had a historic drought in New York City, sparking wildfires in some of the parks that the students enjoy regularly. And you had the return of a former president who believes that all of what we’re seeing is a hoax, threatening the programs and funding that the students were reporting on. His re-election was called just a handful of hours before our class on Wednesday morning, as several students returned from canvassing in Pennsylvania and Michigan.

They didn’t balk at the opportunity. It was a hazy time for a lot of the reasons mentioned, but they found beats that inspired them and delivered five stories each — the most output of any class they’ve taken (or I’ve taught) thus far. We had stories about the coming ‘climate school’ on Governors Island, the merits of textile recycling, and the sustained success of the Battery Urban Farm, tucked away in downtown Manhattan. Students wrote about the prominence of climate law school centers in the second Trump Era, Gen Z’s resolve to end food insecurity, and the role of art in climate protest. We heard about the promise of community gardens, the potential of industrial hemp, and the paradox of dating (!!!) in the era of climate crisis. And we learned about the erasure of vital climate-related data in Project 2025 and unique characters who are trying to address these issues in their own way. (You can read all of those pieces here.)

This is my biannual proud dad moment. But this one carries a specific weight: it was a particularly down time to talk climate, and the students still got through it with grace, drawing inspiration and ideas from the city they live in. Bravo.

Build better

It’s now broadly accepted that we have to construct or renovate most of our built world if we’re going to meet the crises of the moment — a green transition; a housing crunch; a reactive public health system; safer streets; and so much more. That’s the case no matter who’s in office. And if municipalities are going to pull that off at the rapid pace needed right now, the way they’ve done things for decades — let’s call it mid-century modern project delivery — isn’t going to cut it. Too slow, too costly, and, ultimately, too open to fits and starts. (Ezra Klein has based an entire career revival around this concept.)

One of the tools to fix that is what’s known as design-build. I’ve written about it in these pages before, but to summarize real quick: this is the idea that the same company should both design and build a public project. Right now, that’s typically not the case — a product of past anti-corruption crusades, when patrons and cronies landed major contracts for everything from public pools and libraries to sanitation garages and police stations if they paid top dollar to the party machine. To ensure accountability, the process was broken up into pieces, so no sole entity could have full financial sway. This is a good idea, on paper.

But, in reality, what ended up happening is that an architecture firm would design, let’s say, a public pool and then hand it off to a construction company it doesn’t know, who wouldn’t have the right screw for the door, or understand certain engineering quirks — like LED lights that go through the locker room, or an ADA-accessible bathroom — that only that one firm knows. So the project would either be poorly constructed and break later, or the company would have to go back to the firm to figure out the design, or both would have to rewrite it entirely to make it work with what they have. In other word: delays and costs.

This is what design-build looks to address — and it’s something policy research that myself and others have done at the Center for an Urban Future has long called for. (Fuller read on that here.) But in most cases, states have to grant that power to cities, so it’s a legislative slog, especially considering the vested interests who like the multiple contracts. The pandemic, however, shook things, giving lawmakers a very real glimpse of what happens when towns and cities are given emergency powers to erect testing facilities, vaccination centers, food pantries, traffic-calmed streets, and other tactical efforts in a matter of days.

Our research then sparked an agency ‘blueprint,’ which led to a task force, which produced recommendations, which energized a statehouse lobbying push — the classic story arc in the policy-making world. And one of those landed this month, when New York’s governor signed legislation permitting New York City the authority to use design-build on a wider swath of public projects. (A pilot program using the approach has shaved two years, and potentially at least $2.5 million, off of the construction of a new recreation center in Brooklyn named after Shirley Chisholm.) More should still be done — I’ll keep quiet about the lowest-bidder rule — but in this day and age, literally everything helps.

OSA: Seasons Greetings

The 31st Ave Open Street continues to serve as a source of supreme joy in these strange times, as I say so here probably too often. The Open Street — what it hosts, what it adds, and what it means to so many — still just amazes us ‘old heads,’ or the folks who have been around since the pandemic waves of 2020-2021, when it got goin’. That was particularly on high this year, because it was, undoubtedly, our best season yet. Just a well-oiled, well-stocked machine.

And now, as we enter a brief hibernation until April, I’ll briefly bullet-point a few of the things our all-volunteer squad of neighbors was able to pull off this year:

Successfully advocated for a 16-block-long redesign of 31st Ave (work started this summer, and will continue into next year);

Facilitated 37 weekends straight of programming, with a record-setting 150+ public events and 25 markets (that includes our yearly blow-outs);

Donated ~$8,000 to the Astoria Food Pantry from vendor donations;

Built four new tree benches with the Astoria Woodworkers Collective;

Fundraised ~$3,500 to host four summer movies with Tikkun BBQ and the Astoria Horror Club;

Successfully organized for ‘daylighting’ next door on Broadway;

Launched new merch (!);

Grew our ranks to 200+ volunteers and our board to 12 members;

Likely missing something or another there, but that’s the gist and I couldn’t be prouder. In the new year, if you can find a project where you live that allows you to activate or beautify a space with others, or connect to a larger community around you, try to get involved. Believe me when I say: you will not regret it.

Onwards and upwards.

Bright Side: Bollard Picnic

I’m keeping this section nice and brief because it’s the holidays, and let’s be honest: nothing actually serious comes from this time anyway.

Folks who read this missive know I gush over adaptive reuse, which is really just a nerdy way of saying that you’re using something for a purpose other than what it was originally intended for. Adaptive reuse makes our infrastructure more multi-faceted, which, in turns, renders our systems more cost-effective, carbon-savvy, and resilient to change. It’s the built version of not reinventing the wheel. That’s, at least, the serious part; the other part is that it just makes for some really neat stuff. Like this.

The algorithm fed me Amsterbarretje a while back, and I’ve been meaning to feature it here. The end of the year, when all bets are off, felt like a good time. This, to me, is the pure distillation of reusing what’s around us for the better. And bollards are a perfect candidate: these little towers, of metal, rubber or plastic, can be found in towns and cities everywhere. Take a universal activity (having a picnic, or aperitif, or coffee with friends), find a universal piece of infrastructure (bollards), et voilà, you’ve got yourself a readymade solution. Rad.

On the Radar

The Freaks Came Out to Write, by Tricia Romano

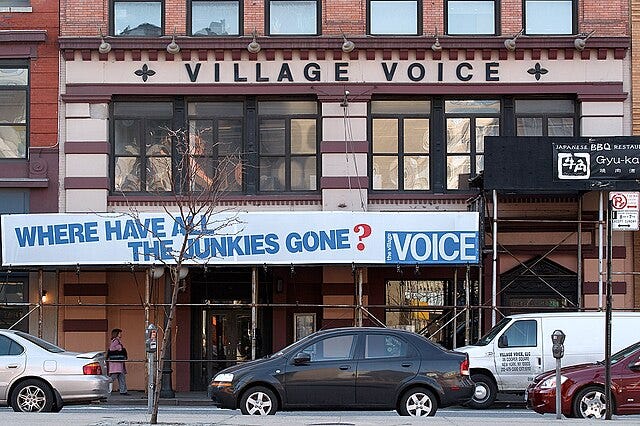

The Village Voice was the first journalism job I ever had, and the first I ever quit. This, however, is tradition. There are very few writers or editors who passed through that paper’s doors without tumult. In fact, it’s a part of its myth: the Voice was messy, just like the downtown culture it exported to small-town America. It was loud, boisterous, unabashed. It was unlike anything else.

The publication, started in 1958 on a shoestring budget, was the country’s first ‘alt-weekly,’ or a newspaper that doesn’t look anything like the ‘dailies’ in terms of style and tone. It was a hallmark of a new form of journalism forming then, which ditched the ‘news pyramid’ taught in journalism school (who, what, when, where and why, in that order) for something more literary and subjective. The Voice was the first to spot the revolutions underway — in dance, theater, music, nightlife, feminism, queerhood, etc. — because it sought out writers from those worlds that other outlets wouldn’t hire due to lack of ‘professional’ experience, and gave them a shot. The paper elevated an everyman in New York City whose politics were hard to pinpoint. The Voice called out the city’s corrupt, but didn’t cozy up to liberal mandate. It rallied with protests, but sometimes found itself in their crosshairs. There was an arts and culture page, but also, a sports page. And sometimes the writers would publicly fight with each other in the ‘letters’ section. The Village Voice defined cool for over 60 years, and tore itself apart in the process.

I, like so many other exurb kids, treated the Voice as sacred text, like my parents had before me. So to be working there barely at the legal drinking age felt too good to be true. I started out in the calendar section, where I wrote blurbs on film screenings, concerts, and other happenings. I was then hired as the weekend editor because I had great editors (hey Araceli and Angela!) who encouraged me to do more. It was where I learned how to write fast; this was the blogging era, where five posts a day was the norm. I had the chance to interview people I admired, cover shows I wanted to go to anyway, and pitch random stuff I found fascinating. Some of my fondest memories in the industry are from those times.

But it was also a wake-up call. Over a decade later, I now teach right next door to the former Voice offices, which is a shell of itself. The publication was savaged by corporate raiders who had no idea how to make a publication based almost exclusively on advertising (it was distributed for free) work in the age of the Internet. (The Voice folded in 2016, and has had fits and (re)starts ever since.) That led to almost sadistically bad management and a shit ton of exploitation. I found myself there during those dark days, and watched as some of the best writers I ever knew got sacked all around me. I ultimately left before I could join them, fed up with the horrific pay and lack of mobility. The place was as exhilarating as it was dismal.

Sorry, I lost track a bit. That period stirs up a real conflict of feelings, as it does for everyone else I knew who worked there. (Thankfully, they’re all off doing amazing work. Voice alum shine.) Ah, yes, the book! I’ve been incredibly heartened to see that strung-up ball of emotions captured so well in Tricia Romano’s pain-staking oral history of the paper, released this year. Romano pieces together reams of live and archival interviews from practically everyone who ever came in contact with the masthead. You hear from the old greats, like the late Jack Newfield and Wayne Barrett, who I owe much of my career to and miss dearly; the provocateurs, like Jill Johnston, Michael Musto, and Greg Tate; the household names, like Colston Whitehead and Hilton Als; and those on the sidelines, like Spike Lee, Keith Haring and Donald Trump. It’s a marvel.

Together, the ups and downs weave this much greater story of how a newspaper was able to be both so radical and relevant — and how it changed American culture in the process. It’s an ode to counterculture, progress, and the soul-searching it takes to get us there. Long live The Village Voice.

Note: This book was gifted to me by a former student, Ethan Beck. Thank you dearly, Ethan — you would have made a great Voice critic.

Streetbeat Gig Board

The Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice, City Hall’s office for all things climate-related, is hiring a few senior advisors. (New York, NY)

New Yorkers for Parks, the citywide outfit for parks advocacy, is looking for a director of development. (New York, NY)

One of my favorite outlets for climate reporting, Grist, is searching for a climate news fellow for the summer of 2025. (Anywhere, USA)

***

Design Build is great in streamlining many aspects of building but it’s not without risk. Because results still depend on a thorough, competent design prior to the build. And that’s not always the case. When the design, for example doesn’t consider the requirements for new fire hydrants until after the build it’s a case of do-over at great cost of time and money, often necessitating demolition of parts already built. I know of at least one case where this happened. Would the traditional process have caught this? Probably but screwed up in many other ways that are well known.

Design- build should be audited so those using it can learn from mistake, publish them, and everyone can learn and develop punch lists to avoid mistakes and insure high quality.

Finally, experience also often matters as much as expertise in any building project. The ability to spot trouble early and pivot also has a lot to to with faster buildings.