Waah Oud De Na*

And welcome to this newsletter.

It's where I (John Surico) talk each month about cities & their discontents: streets, climate, cultures, people, food, form, etc. This month, we cover:

- Communicating policy wins;

- A proposal for parks funding;

- The new drivers of climate progress;

& much, much more.

Programming note: Wow, Streetbeat is officially five years old this month! I’ve said this repeatedly (probably too often), but this newsletter and the folks I hear from about it brings immeasurable joy—truly, truly, truly. And now it’s surpassed the thousandth subscriber mark, I’ve been thinking a lot about ways it can grow and improve. Long-term, I’d love to feature guest writers, videos, and themed editions—which is honestly just a bandwidth issue, at this point. But short-term, I want to translate this stuff into various media, so it can reach more people.

So taking a page from one of my favorite Substacks—Sarah Barnes’ Along for the Ride—I’m going to flip a voiceover of this very newsletter, where I’ll read aloud text for *all the audiophiles* out there. And I’ll keep it short, likely 20 minutes or less, with maybe some tangents. Things happen when you talk it out!

If you do decide to listen (above), let me know what you think, plz + thank you ✌

Running in circles

Perhaps the greatest lesson from America’s last election (and believe me, there were many) was that policy doesn’t win the day. If that were the case, things would look a bit differently right now. You can uphold a great 'win,’ and it really could be a good thing, but if the voter doesn’t feel like whatever you did helped them directly, or reversed their fortunes in some amorphous way, it’s as good as dead, at least in terms of helping you at the ballot box.

Now, that’s not to say you shouldn’t do it; majoritarian democracy is scary, for a reason. And thankfully, there is a steady shadow government, who enter public service to actually help people, that continues to hum along, subtly advancing smart policy at the lower rungs. But 2024 was a warning shot to not rest on these ‘achievements’ as a fail-safe, and a very visceral reminder that communication is 75% of the game. (I have so much to say about how this relates to the start of congestion pricing in New York this month, but that’s for February!)

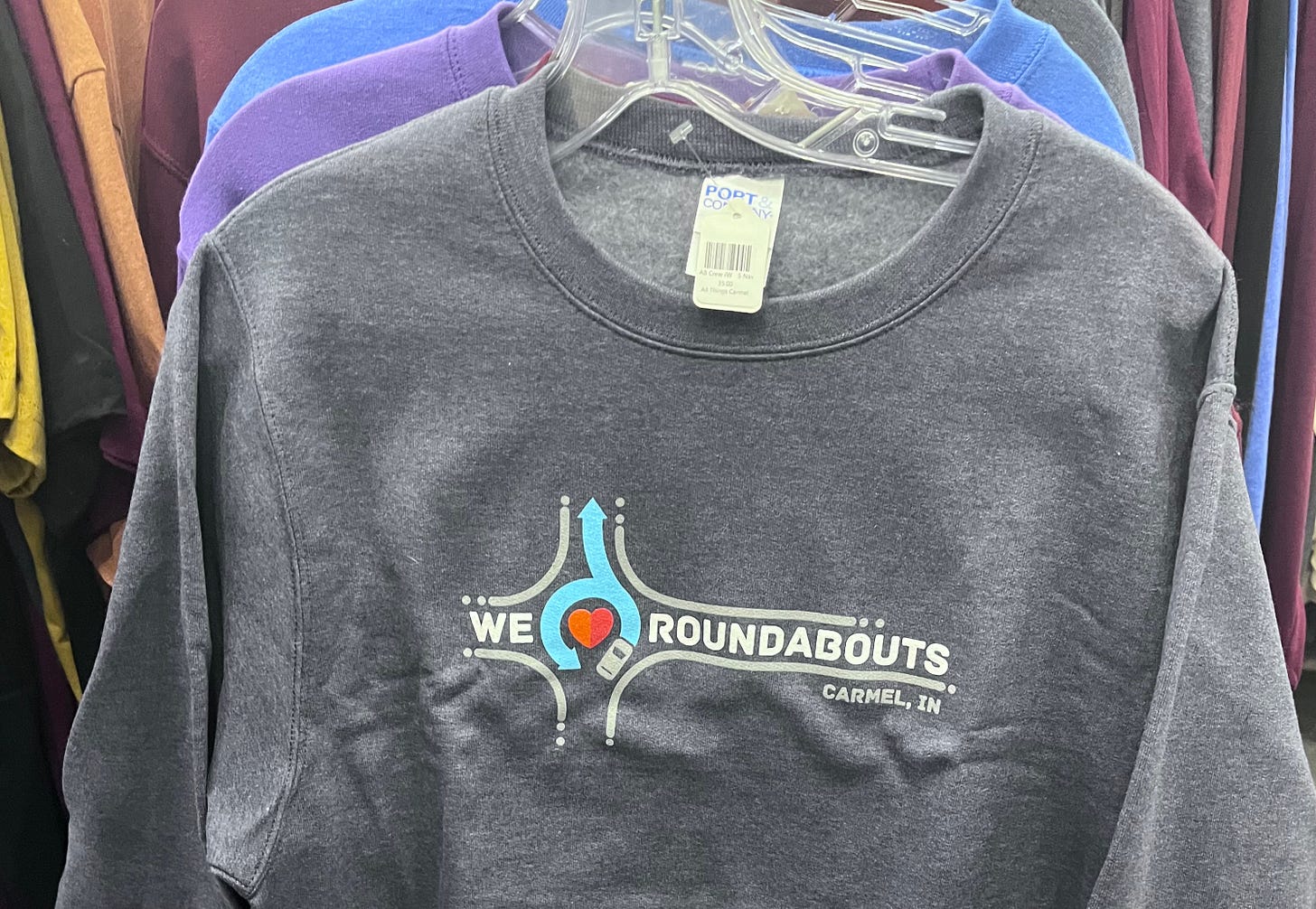

Case in point: Ashland, Kentucky. My editor at Bloomberg CityLab (shout-out to David!) asked if I could look into something strange that happened there this last year. A group of city commissioners and planners in the small Appalachian city wanted to make their downtown stretch safer and more walkable for all. The result was a streetscape makeover, including the installation of five roundabouts and the conversion of four traffic lanes to two, which is now nearly complete. Their hope was that a more attractive corridor would bring greater foot traffic, thus more businesses and people, which the town desperately needs.

But instead, all but one commissioner—and another who was running for mayor—lost their respective elections. They blamed the roundabouts.

As I dug in more, this hyper-local story felt like a microcosm of where the American populace finds itself today: deeply skeptical of government, distrustful of facts and statistics, and generally cautious of change. And while it may seem that a circle where cars have to yield in perpetuity isn’t the same as, say, climate or immigration policy, I’d argue that street design changes are, in fact, some of the greatest provocations. That’s because of their routine tangibility: you have to pass through it on your daily drive. (Just like one sees inflation because you have to buy groceries.) That has consequences, and the folks in Ashland, Kentucky learned the hard way.

So I spent some time chatting with them and a few experts about how beneficial policy actions like roundabouts—which, objectively, save lives—can reach a weary public. Here’s what I found out.

Ticket to ride

I spend a fair amount of my time these days trying to figure out ways to pay for parks. See, New York City is the place that pioneered the ‘private park operator’ model—in the wake of the 1970s fiscal crisis, Central Park Conservancy and Bryant Park Corporation were both formed to harness private wealth for public good; Central Park, from wealthy benefactors who lived nearby, and Bryant Park, from adjacent businesses. They laid the groundwork for similar models to follow: Brooklyn Bridge Park, which funds its operations through windfalls from properties on site; Domino Park, which was built—and now maintained—by a developer; and The High Line, which receives zoning bonuses from the condos that sprung up alongside it, to name a few. But what we haven’t been able to crack is how to pay for every other park.

In January of last year, Eli Dvorkin and I put out a policy report with Center for an Urban Future (CUF) that detailed 20 potential revenue streams for the city’s parks system. It took inspiration from elsewhere, since seemingly everywhere I looked, cities were crafting smart, sustainable sources of recurring dollars for parks, especially in the wake of their pandemic-era renaissance. Except us. We got press coverage, held a forum, and rang the alarm as the city’s Parks Department absorbed a $20 million cut. (I wrote all about it then, for brevity.)

Shortly after, we received support yet again from the NYC Green Fund to take two of the ideas and really run with them. The first we chose was one that attracted the most attention: a modest surcharge on tickets sold at stadiums located on parkland, which includes Yankee Stadium, Citi Field and the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, where the U.S. Open is held. (The second is on expanding concessions in parks—more on that later this year.)

How, exactly, would that work? This is a rare question for a policy organization to answer—our job is to research and form ideas (hence the term “think tank”), not tell folks how to enact them. But it was a fun exercise nonetheless. Instead of parks experts, I spoke with tax law, municipal finance and budget experts. Our team, which included the great work of research assistant Nicole Lu, crunched the numbers on what different percentages would generate, and what would happen if the surcharge covered Broadway, sporting events, and shows. And we laid out a legislative path for state and city leaders. The result is a policy brief, which I peg more as an action plan, to enact a ‘Parks Improvement Trust,’ which, if passed by lawmakers, would be the first-ever direct funding mechanism for parks citywide. You can read it here.

We’ve been busy since then. A panel we held with parks advocates this month attracted over 150 people, with helpful points made around advocacy, messaging and inclusion. A few different outlets covered the proposal. And we received sincere interest from two elected officials in Albany to sponsor legislation in both chambers—the first step in the process we outlined. Election-year politics prove tricky here, especially with affordability a central theme, but we’re excited just to start the conversation. Stay tuned to where it goes next.

Decarbonize the campus

After a spree of spending on the ‘green transition’—in the United States, the European Union, China, Africa, and elsewhere—the world is returning to a time when substantial climate progress will be driven by localities or the private sector. That shift can be attributed to multiple phenomena at play: the resurgence of far-right and nationalist parties worldwide; legitimate concerns around the cost of living; a general dismay towards international efforts, like the Paris climate accords; and other global conflicts taking priority. For what it’s worth, sucking the oil out of our existence was always going to be bumpy—but the good news: it’s underway. Just who’s leading it is going to change for a bit.

When devolution like this happens, the onus is on regions, states and cities to generate funding, restructure regulations, and pass laws. Right now, what these places need to reckon with is the actual power they have to make change, and how the hell they’re going to pay for it, using primarily the money that circulates through their own economies. But I’d argue: that’s what they’re best at. I like to remind folks that some of New York’s most ambitious climate laws—the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, which legally mandates reductions, and congestion pricing, which charges drivers to enter Manhattan—both came during the first Trump administration. That was not happenstance.

Neither was a recent announcement from New York’s governor, Kathy Hochul, who proposed applying a portion of the Environmental Bond Act—a $4.2 billion measure for climate spending, passed by voters in 2022—towards decarbonizing the state and city’s aging public universities. Last April, Eli and I called for exactly that in a commentary at the CUF about the City University of New York (CUNY), whose aging buildings and their renovation could provide a generational opportunity for green job training and learning. (More details here.) We also said Washington had a major role to play.

But now, in a political landscape where that’s just not possible, the state finds itself back in a familiar position: front and center.

Orientation

This year’s version of “Advanced Reporting: The City”—a capstone-level reporting course I teach every spring, focused on covering urban issues—came with a caveat: New York City has entered its most unpredictable period since March 2020 and, before that, September 2001.

Its mayor, facing down indictment and a rocky re-election, is weighing his futures, which range from resignation to Republican Party re-registration.The president, seeing red in a historically blue sea, appears emboldened to assert the executive office onto his hometown, deploying federal agents, tying up federal dollars, and upending federally-approved plans. (I wrote about what that could mean in November.) The city itself is mired in a multitude of crises—ones of health, housing, affordability, climate… the list goes on. We have entered a year not knowing how Gotham will fare by its end. Everything feels up in the air.

That’s the reality the undergraduate seniors have entered—the same cohort whose college experience started in the midst of a debilitating pandemic. From what I can glean the first few weeks of class, they recognize these stakes and are eager to write those stories. And I’ll be sure to share them here.

OSA: Foot traffic

For as long as I have lived in Astoria, Queens—which hit a decade (!) last year—the storefront at the southwest corner of 31st Avenue and 35th Street has been vacant. But a few months ago, it wasn’t any more: Coffee Lab, a sleek nouveau café, opened there, its front window featuring stools and a bar that faces the street. Long operating hours (6am to 8pm) add a welcome presence in early mornings and evenings, especially in the dark of winter. It’s already busy.

With Coffee Lab open, only one other vacant storefront on the block—the sorely missed Zenon Taverna, the first restaurant I ever ate at in the neighborhood— remains. On the next block down (33rd to 34th Street), there’s only one, too. So, effectively, we’re at 80 percent occupancy on the Open Street.

That echoes statistics shared recently by the city’s Department of City Planning in a new report on storefront vacancy. Occupancy is up across the board—good news after the pandemic downturn—but it’s notably higher somewhere in particular. Here’s the passage:

“Storefronts along Open Streets experience a 9.9% vacancy rate, lower than the citywide rate of 11.1%. Open Streets are seeing greater recovery to pre-Covid vacancy rates, and many Open Streets are experiencing vacancy considerably lower than their surrounding neighborhoods as a whole…”

It also shows the reverse: public space obstructions actually depress occupancy rates. Check out the contrast:

Storefronts underneath scaffolding have a 17.6% vacancy rate, a rate significantly higher than that of the citywide average.

Together, the findings offer a greater understanding of how we navigate places: when we like being somewhere, we’ll stay a while—and so will our spending, attracting attention from businesses. And what makes us want to be somewhere? Studies tell us plenty, but we know already, right? Safety. A sense of calm. Maybe a little greenery. Somewhere to sit. Activity.

Towns and cities aren’t going to shape larger retail trends—but what they can do is invest in fostering diverse, vibrant places. And, doing the math, that might be the best bang for their buck.

Bright Side: Car Wash

In line with last month’s bollard-à-bench, here’s another bit of inspiring reuse: a group of industrial design students at Georgia Tech retrofitted a retired school bus into a ‘Mobile Laundry Bus.’ The seats were replaced with washers, driers and showers; water tanks were added; and electric was rigged from the battery.

The idea was Nicky Crawford’s; he runs Flowing with Blessings, a nonprofit that provides services to the unhoused in Atlanta. He wanted to address the heavy stigma of hygiene in shelters and amongst the public, but he needed something that could move around, mirroring the population he serves. So Crawford purchased the bus, and approached the school to help execute his vision.

To date, the bus has cleaned the clothes and offered showers to over 4,500 individuals. When operating, it can see about 60 people a day.

On the Radar

The Library Book, by Susan Orlean

***

New Yorkers share a pre-existing condition: they have feelings about L.A.

The traffic is a mess. Nobody walks. Everybody drives. Everything is far. It’s impossible to make friends. It’s clique-y. There are no seasons. The only industry is Hollywood. I don’t care about celebrities. California is… California.

Every New Yorker is guilty of griping about the other coast—and that includes me. But as time has gone on, I’ve warmed up to the place. I attribute that to a few factors: the many friends of mine who live there, who, knowing my prejudices, have dutifully showed me around their respective nabes; its incomparable food scene, which I learned about from fab writers like Tejal Rao, Jonathon Gold, and Dana Goodyear; the ambitious work underway to expand public transit and improve parks, which I’ve seen firsthand myself. And this month’s passing of the great David Lynch reminded me of the countless movies set there that I adore, including his own Mulholland Drive. (The City of Angels is truly its own genre.)

But that journey started with The Library Book. It’s about the immolation of the Los Angeles Central Library in 1986—the worst library fire in modern times, on the scale of Alexandria. Forty thousand volumes burned. And Susan Orlean, a recent transplant, becomes obsessed with figuring out who or what caused it. (It remains unsolved to this day.) What results is this heartfelt homage to libraries as rare democratic spaces, sure, but also, the rich complexities of this sprawl sitting along the Pacific: its history, design, and people.

Of course, this month, I was thinking of another fire that threatened the city—this one less by man or mistake, but by nature herself. And like so many other New Yorkers, I felt powerless watching from afar, not knowing what to do other than message loved ones and assure that they were safe. Lives are gone. Homes are gone. So much of what makes L.A. L.A. is gone. And I don’t know what else to say but: support mutual aid, support advocacy, and support the city.

Streetbeat Gig Board

The tactical urbanism team at Street Plans, who I had the pleasure working with this last year, is looking for a designer. (San Francisco, CA, or elsewhere)

Centre for London, which does some of my favorite policy work across the pond, needs a senior events organizer. (London, UK)

The Horticultural Society, the entity who helps steward the 31st Ave Open Street and so many other public spaces, is hiring. (New York City, NY)

The Big Dig blessed the world with the lovely Rose Kennedy Greenway, and they have a few internships available. (Boston, MA)

***

Audio sounds great!

Love the audio!