خوش آمدید*

And welcome to this newsletter.

It's where I (John Surico) talk each month about cities & their discontents: streets, climate, cultures, people, food, form, etc. This month, we cover:

- The race to be New York City’s next mayor;

- Funding five years after the pandemic;

- How mutual aid can save lives;

& much, much more.

Platform shift

Later this year, New Yorkers—or, at least, some fraction of them—will choose their next mayor. And, to put it bluntly, the race is a shitshow. With record-low approval ratings, sagging even further after it became quite clear that he cozied up to the president to see his corruption charges dropped, the current City Hall occupant (Eric Adams) may run as an independent, if he even stays in. The former governor (Andrew Cuomo) is leading the pack, with a campaign fueled on the hope that New Yorkers have short-term memory. An insurgent socialist (Zohran Mamdani) has cemented himself as the election’s progressive darling and a top contender. The head of the city’s legislative body (Adrienne Adams) joined the fray to little fanfare. And a potpourri of liberals (Brad Lander, Jessica Ramos, Zellnor Myrie, Scott Stringer, Michael Blake) are vying to be everyone’s third or fourth pick. (New York City has a ranked-choice voting system.)

Through a variety of measures, public space is on the ballot. The future of Open Streets seems unclear—which I’ll explain later. People are noticing that city’s pandemic-née-permanent curbside dining program is a shell of itself since it went seasonal. Congestion pricing, now in its third month, has knock-on effects for how we can rethink our streets, but it remains threatened by Washington. On the world’s stage, New York has fallen far behind the rollout of busways, bike lanes and car-free zones. (For comparison: Paris just voted to pedestrianize 500 blocks.) And all of that is unfolding in a post-pandemic paradigm where a growing chorus of politicians, business leaders and planners recognize that a robust public realm underpins a thriving urban economy in 2025.

I’ll be keeping tabs on the race as it relates to the conversations I have here. In the meantime, I was excited to advise on the Urban Design Forum’s Vision for a Better City, an ideas blueprint for candidates on the issues that matter most to urban designers, planners, and practitioners. Like making it easier to activate and care for public spaces, improving their design, and actually giving them the funding they so desperately need. Now begins the process of parsing out campaign promises from actual policy commitments.

(On a related note: my cohort for the Forum’s Rewire initiative last year penned an op-ed on our idea to transform the city’s peaker plants into biodiversity hubs, which was recently published in City Limits. Check it out.)

On the radio

I aired most of my thoughts on congestion pricing here last month. Not too much has changed since; if anything, it’s only been baked further into the cityscape: honking complaints are way down, Access-a-Ride and bus speeds keep rising, and Broadway is experiencing a mini-renaissance. (There’s also a lot of revenue pouring in.) As I’ve reported previously, the longer that all drags on, the harder it will be to undo. But if you do want to hear a bit more context to the drama surrounding the most profound challenge to America’s car culture in our lifetime, I returned to The Outspoken Cyclist podcast to chat with host Diane Jenks about the courts, the White House, and the other complicated chapters of this never-ending story. You can give it a listen here.

Alternate streams

The bulk of my waking hours is still dedicated to devising ways to better fund New York’s parks and open spaces. And that work increasingly feels urgent: the city faces a budget deficit of at least $8 billion in the years ahead, and when this happens, parks have been first on the fiscal chopping block. Then there’s the specter of spending cuts from Washington. What’s Trump got to do with local green spaces? Not much. But Biden’s infrastructure and climate bills colored Gotham green in grants for things like street trees, a new linear park in Queens, and jobs training. And now those dollars are in political purgatory.

Our latest proposal at the Center for an Urban Future: a thoughtful expansion of concessions, with more of the money they generate staying in the parks they’re based in. (Seems sensible, right?) I’ll have a whole lot more to say next month when the brief’s out, but if this is as much of a tantalizing topic for you as it is for me—hands up if you enjoy a coffee in a park!—then tune in virtually or stop on by IRL to a forum we’re hosting this Wednesday at WNYC’s Greene Space, where I’ll join the leaders of some pretty renowned green spaces and other experts for a panel on the potential of parks concessions. RSVP here.

Our other recent proposal—a modest surcharge on ticket sales that would directly support parks maintenance—is the tougher slog, just given the politics. (Which grew fuzzier this month with the protest resignation of the city’s deputy mayors.) But we were delighted to see the idea included in the legislative platform put forth by Alliance for Public Space Leadership (APSL), a collection of influential advocacy groups in New York. The dominant narrative emerging is this: with the stakes this high, something’s gotta give.

OSA: Funding

Pandemic-era programs have always walked a tightrope. Sure, you can enshrine something into law, but it’s up to leaders, expending the appropriate amount of resources and capital, to actually see it through. (Also: times change, and so do those leaders.) Hence why we’ve seen so much disappear (remember the child tax credit?) or get diluted (or Build Back Better?). If you read even an iota of the Covid five-year anniversary content out this last month, one uniform message rang clear: we, collectively, squandered a generational moment to think big. Making it last is the real challenge. Progress alone is fragile.

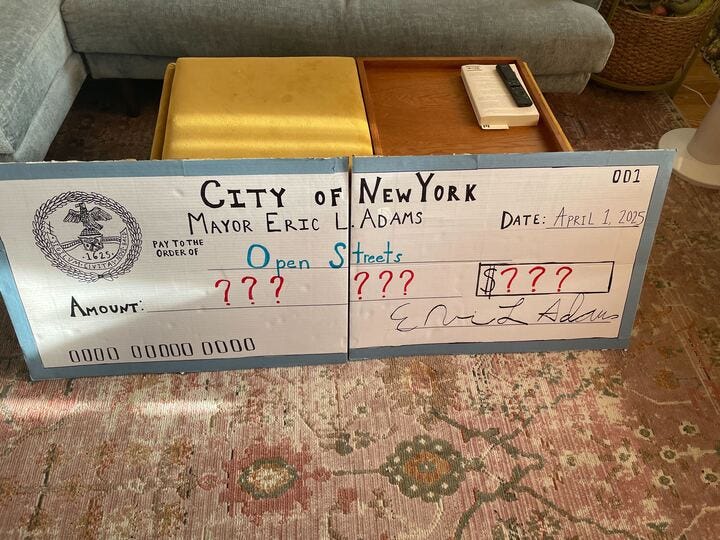

To that effect, a telling moment came recently: half a decade after it started as an emergency response to a public health crisis that made outdoor space scarce, the Open Streets program is running out of money. The pandemic relief dollars from Washington have all but dried up, and there is no definite plan to replace them in the city budget. Add in the already shaky ask of volunteers to pull off an intensive program and a generally blasé, if not sometimes outwardly hostile, attitude from City Hall, and you’ve got yourself somewhat dire straits.

But pressure isn’t always such a bad thing. An implicit warning from city officials about future finances helped spark the biggest rally yet for Open Streets, where organizers, advocates and local leaders came together to call on the city to fully fund the program with almost $50 million over the next several years, which would pay for their upkeep and expansion. (I couldn’t be there myself, but the team from 31st Ave Open Street Collective helped in advance with outreach and letter drafting.) It forced our vast array of (largely volunteer) partner organizations—who have sounded the alarm for some time now—to align on a single message, make it an issue in the mayoral race, and take to the streets in full force. Now, we wait to see how that work pays off in budget negotiations.

In other news: the 31st Ave Open Street’s fifth season starts Saturday, April 26th.

Bright Side: Lives Saved

This is a newsletter about cities, so I don’t normally write about the scourge of substance addiction here. But about a third of Americans know someone who has died from opioid addiction, and I am one of them. I’ve attended my fair share of wakes and funerals that should’ve never happened, where the cause of death listed is either vague or left blank. My hometown, like much of Long Island, succumbed to successive waves of barbiturates, heroin, and, most recently, fentanyl. And their addiction has impacted countless loved ones close to me.

Like traffic fatalities, drug overdose deaths had largely plateaued until about the mid-to-late aughts, when opioids became vastly accessible thanks to a web of bad actors. (The Sacklers, Big Pharma, greedy doctors, and America’s deeply broken healthcare system, to name just a few). We went from 10 to about 30 deaths per 100,000 people in just 20 years. That’s the equivalent of 200 more people dying each day. The pandemic, of course, only made matters worse.

You might be asking: where’s the good news? Well, something is afoot. After a peak in 2023—where 300 people died of drug overdose each day in the U.S.—the numbers are suddenly dropping. This last year saw the fewest drug overdose deaths since June 2020, with a 24 percent decrease in total deaths, from 114,000 to 87,000. It’s a one-year decline never before seen by public health officials.

Again, why write about that here? Because a top reason cited by experts for this precipitous fall is the distribution of Narcan en masse. In a brief period of time, tons of Americans got their hands on tiny kits of naloxone, which can resuscitate someone in the throes of synthetic opioid overdose. The nasal spray is available in pharmacies, health clinics, and district offices; it’s typically stocked at raves, festivals, and parties; and it’s now common to see at people’s homes, next to first aid. (Related: our Open Street team is trained in its use, and regularly hand it out.) Like vaccines and food aid, it’s a testament to mutual aid, where resources are made easy to use, cost virtually nothing, and placed directly into the hands of as many people as possible, without institutional barrier. The bottom-up approach is now saving about 70 more lives each day. Just… wow.

On the Radar

The Wrecking Crew, by Thomas Frank

Each day, Americans have front-row seats to the systematic dismantling of their government. Over the last three months, thousands upon thousands of civil service workers—the people who regulate banks; the people who make sure our food doesn’t kill us; the people who distribute medicine to developing countries—have been fired. There has been perhaps no other time in this nation’s history where an insular circle of elites pulled off such a swift Barbarians at the Gate-style raid of post-war bureaucracy, with implications so vast and debilitating, it’s difficult to keep track of just what, exactly, is happening.

But while it may seem without precedent, there is a playbook for all this. In the 1980s, the ‘Reagan Revolution’—using terminology that the MAGA tent would later borrow (“Let’s Make America Great Again” was Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign slogan)–swept into D.C. with what it viewed as a mandate to drastically shrink the size of government, fueled by discontent with 1960s-era social expansion and 1970s-era economic stagnation. But instead of abolishing agencies, which takes an act of Congress, Reagan’s troops chose a different tack: hollow them out from the inside. Lay off employees. Don’t fill their positions. Neutralize core functions. Deregulation through starvation.

If there is a book to understand this moment in American history—and this goes to readers abroad, too: if you don’t think it can happen where you live, Trump is writing the manual—look no further than Thomas Frank’s The Wrecking Crew. (Frank’s other seminal text, What’s The Matter With Kansas?, which explores how conservatism won over the working class, is also a must-read.) In painstaking detail, Frank deconstructs how a pack of right-wing businessmen and ideologues ganged up to stack federal agencies with people who simply didn’t believe they should exist. It all then came crashing down, usually (unsurprisingly) to the financial benefit of the saboteurs.

But Frank’s real message is what that does to the public sector. A decade of picking off government bit by bit shoved the U.S. (and elsewhere) into the neoliberal age, where government was seen as “the problem, not the solution.” Bureaucracy failed because it was designed to fail, greatly shrinking Americans’ imagination of what Washington could do for them. This persisted for some time, with Clinton’s centrism in the 1990s, Bush’s neoconservatism in the 2000s, and Obama’s liberalism-lite in the 2010s. The Eighties set the tone for what was possible, and it wasn’t much. And only recently, when Biden’s agenda staffed up agencies to enact a scope of work not seen since the Great Society, did that shift.

Like the wrecking crews before it, ‘DOGE’ is responding to what it perceives as a threat; this naked pursuit of profit under the guise of ‘efficiency.’ History is merely repeating itself, only this time at a much faster clip. And unless opposition is stiff, Frank teaches us, it’s going to leave a mark.

Streetbeat Gig Board

Transportation Alternatives, the street safety heavyweight, is hiring for a national communications and policy director at Families for Safe Streets and a director of development. (Remote; New York, NY)

If smart policy concerning urban safety and criminal justice in New York City is your forte, Vital City has a job for you. (New York, NY)

More climate comms positions! (All over)

Second Nature, a think tank that focuses on climate and higher ed, is looking for a new climate policy fellow. (Remote)

Regional Plan Association, probably the most influential civic group in the tristate region, needs a transportation associate. (New York, NY)

***